Human First Inspirations

Filmstack Challenge: Day 34

Welcome everyone. For those of you unacquainted, the FilmStack Challenge is a communal writing endeavor started by Ted Hope to rally the “Nondependent” film makers writing here on Substack together and get us acquainted with one another. Maybe in the process we’ll get our own Substack category of “cinema.” I think I had to settle for “arts and illustration,” when selecting mine, so that would be a real win as well. I am a big fan of what Ted Hope has been building here on Substack and in getting to read about what is inspiring other filmmakers with whom we are all on this journey together. For my leg in this journey I just want to briefly share three works which have left an indelible impression on my own approach to filmmaking.

A documentary short: Glass

The glass blowers’ hands move over their tubes like Jazz musicians lovingly playing their instruments. The filmmakers might as well be playing right along with them, and no less confidently or lovingly. No words, no fancy gimbals, no camera movement at all beyond tracking a subject. Just a tripod, a 35mm camera, and the perfect match of subject and sentiment. Edited with total self-assurance, it came out in 1958 and it hasn’t aged one day.

In this film there is no sense of “B-Roll.” Rather, every image feels as if it was shot in perfect relation to the overall vision. It so captures its characters that the need for words at all completely disappears. May we all aspire to such assurance. I do not know what the methods were for making this film - whether the juxtaposition between hands spinning the glass blowing tubes, and the sound of instruments being played was conscious at the time of filming, or only discovered later during the editing, but whenever this emerged it is clear how playing out its implications gave the entire piece its structure and charm. I have been frustrated in the past by “b-roll” sessions when myself or the client has no particular aim, no sense of how to see a subject in relation to the vision of the project beyond capturing something beautiful and cinematic. I find myself constantly reframing, doubting my image, cutting often, and in the end missing important moments. This film is thus a reminder to me how elegant and simple truly beautiful cinematography can be when it flows from the film’s central idea. The artistry of film lies in truly seeing a subject and letting its essence inform your idea such that all other ways of seeing a ruled from the first frame.

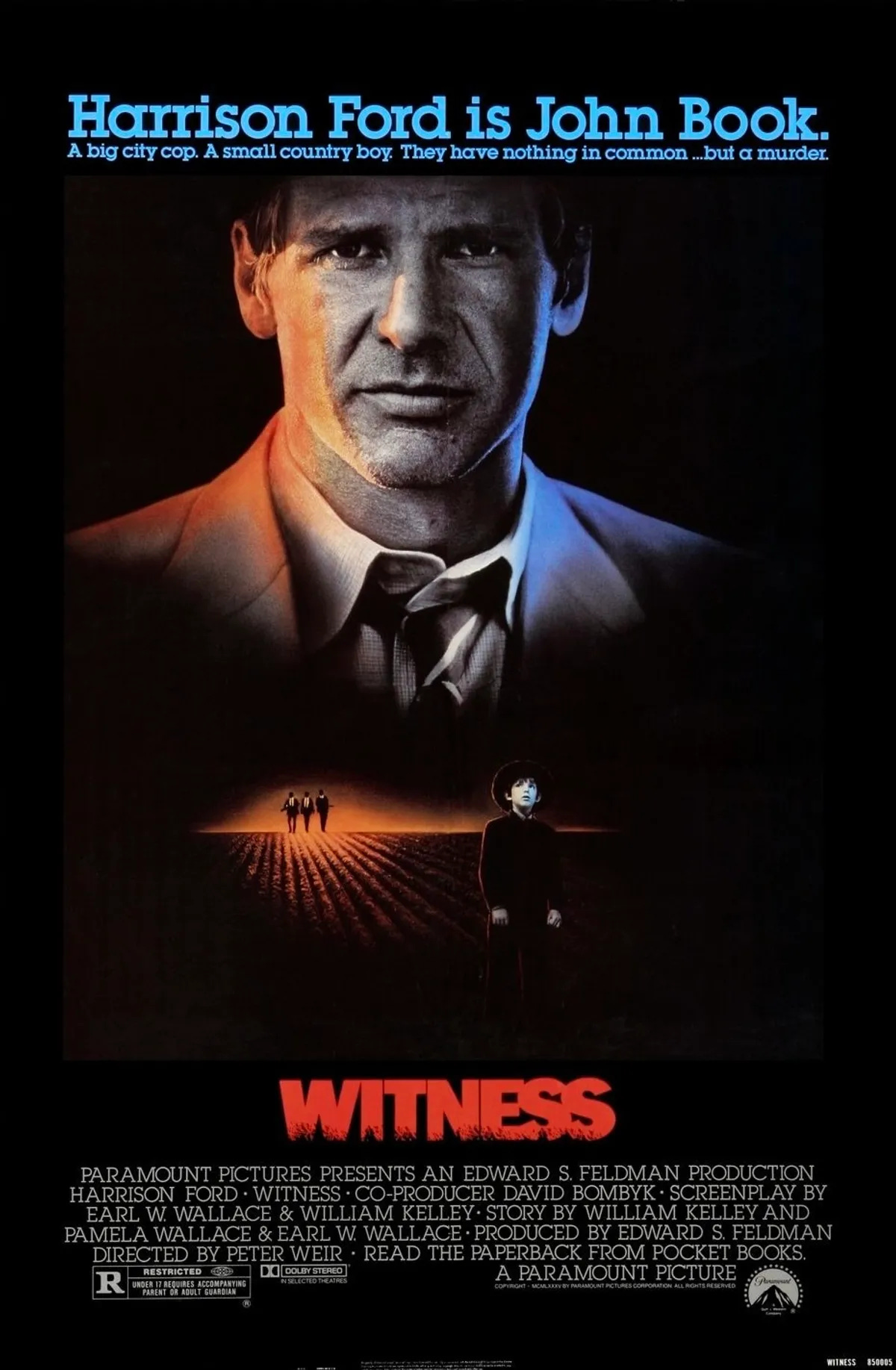

A feature film: Witness

The film that has lived rent free in my mind all of 2025 is Witness. Peter Weir, Harrison Ford, Kelly McGillis, and the entire team elevate what could easily have been a mere police procedural to a quiet classic about a worldly detective forced to hide out in a decidedly unworldly Amish community.

Growing up in the early 2000s and watching the Making of featurettes on DVDs, I’d often find myself saying, “I can’t believe what they can do with special effects.” These days, when I watch Witness, I say to myself, “I can’t believe what actors can do.” Certainly, if such a film were made now, the effort would be to film within a real Amish community (assuming they would ever assent to this) and that would be remarkable for its own reasons. But it is simply amazing to me that there is not a single Amish person in the film, that every single one is a hired performer, (be on the lookout for a young Viggo Mortenson) and yet the respectfulness of the portrayals and their inner depth are so compelling as to completely win one over. It’s a real testament to the reality that could live on the frame when Hollywood was working at its best and when great teams come together.

Though there is nothing formal that would make this film impossible to make now, it is a bittersweet thought to me that this kind of film is so hard to imagine existing in our present time, and I have spent a lot of time thinking about why that might be.

The Building the Barn sequence is a perfect microcosm of the whole film, and maybe even of life itself. It reflects the kind of communal living and human connection through faith, labor, and food, and the quiet, unspoken unfolding of love, that looms wistfully just beyond the veils of memory.

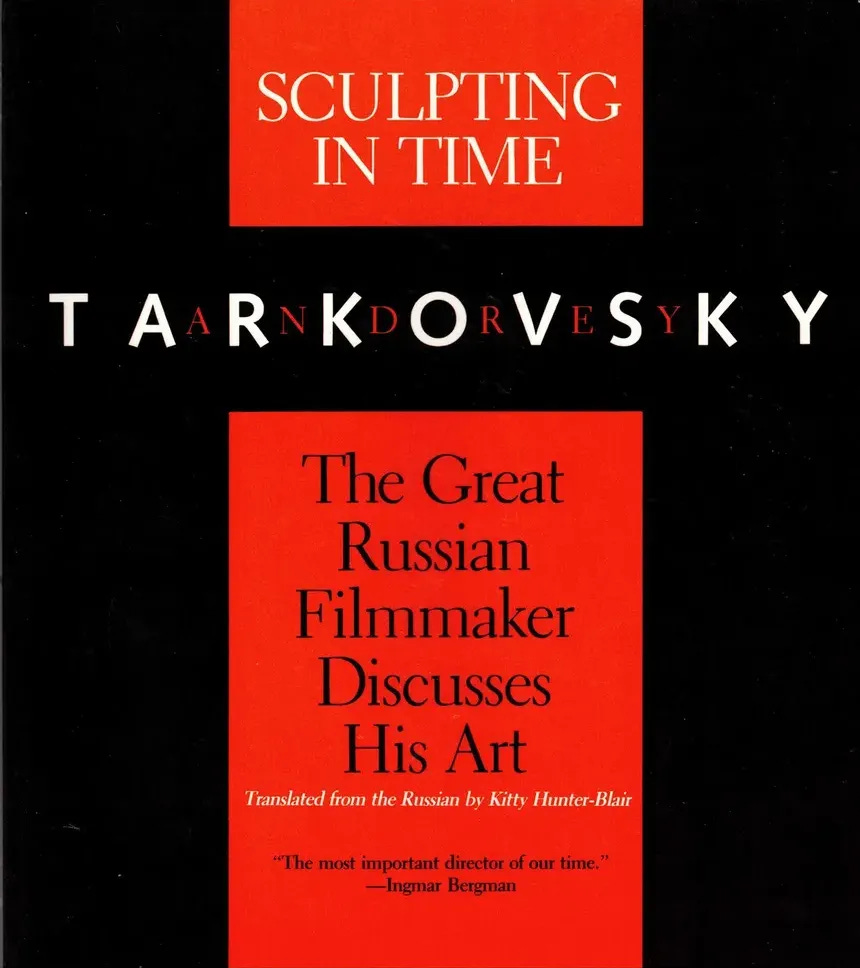

A book: Sculpting in Time

I am not original in loving the great Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky’s book and sometimes memoir Sculpting in Time, but there is simply no book on filmmaking that I have come back to as often, no work that I have read which speaks so directly to the essence of the artist’s journey through life, and the challenges that one must face when all the forces of the world demand you to compromise.

In Sculpting in Time we learn that Tarkovsky’s style is not simply an aesthetic to be aped – dolly shots in forests, and the backs of people’s heads looking pensively into the distance – it is a total vision that arises organically from his unique way of seeing the world. Tarkovsky believed that cinema’s unique offering to the world was nothing less than the experience of the passing of time and the ability to portray and to modify its flow. He constructed his work to take advantage of this and to fully immerse the viewer in this uncanny sense of time’s passage.

“Why do people go to the cinema? What takes them into a darkened room where, for two hours, they watch the play of shadows on a sheet? … I think that what a person normally goes to the cinema for is time: for time lost or spent or not yet had. He goes there for living experience; for cinema, like no other art, widens, enhances and concentrates a person’s experience – and not only enhances it makes it longer, significantly longer. That is the power of cinema… What is the essence of the director’s work? We could define it as sculpting in time.”

-Pg 63

Sculpting in Time is not simply a text book of Tarkovsky’s theories of cinema, more importantly, it reveals the soul of a deeply principled artist who managed to make uncompromising films of timeless significance in an atmosphere of total repression under Soviet Censorship. It indeed seems like a miracle that any of his immensely personal and idiosyncratic films could exist in such an ecosystem, but he hardly ever expresses bitterness about his circumstances. I know of no other filmmaker who so fully articulates the immense inner resources that a director must possess and cultivate in order to make lasting work. It will be of interest and encouragement to anyone who must navigate the path of an artist.

In order to be free you simply have to be so, without asking permission of anybody. You have to have your own hypothesis about what you are called to do, and follow it, not giving in to circumstances or complying with them. But that sort of freedom demands powerful inner resources, a high degree of self-awareness, a consciousness of our responsibility to yourself and therefore to other people.

Alas the tragedy is that we do not know how to be free - we demand freedom for ourselves at the expense of others and don’t want to waive anything of our own for the sake of someone else: that would be an encroachment upon our personal rights and liberties. All of us are infected today with an extraordinary egoism. And that is not freedom; freedom means learning to demand only of oneself, not of life or of others, and knowing how to give: sacrifice in the name of love.

-Pg 181

See you out there.

- Bryan

Your musings about The Witness makes me want to revisit the film. I long for authenticity and it’s so hard to find in today’s films. Plus, I find the Amish people fascinating.